Possibilities of AI for Research and Teaching – Case Study of Media Production

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming how research and teaching are conducted across scientific institutions. At the Helsinki Institute of Physics, we have explored its possibilities both in academic work and creative projects. This post first examines concrete uses of AI within our institute and then presents a case study from CERN’s media production.

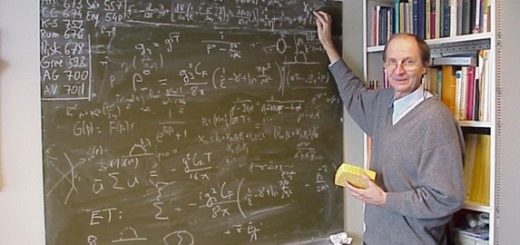

Practical Experiences with AI at HIP

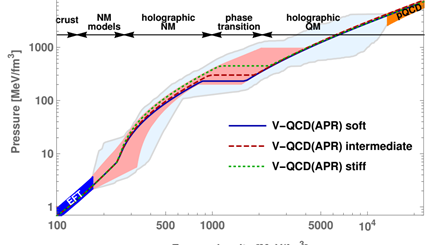

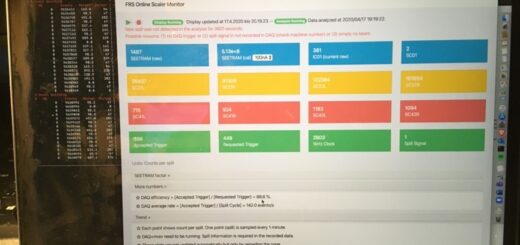

In a physics research institute environment, AI applications already have many potential uses. Software development is one good example. AI can help understand and produce code in various programming languages, sometimes even better than an average programmer.

For example, GitHub Copilot is an AI-based tool that assists in writing and debugging code. There are also platforms like Siml.ai, which combine AI with physics simulations, allowing faster and more efficient results. In addition, tools have been developed to support learning programming specifically for physics simulations. AI can also optimise complex experimental setups and control, for instance, laser systems.

Report writing is another area where AI can provide assistance. There are AI-based tools that can summarise research papers and act as writing assistants. Other tools have been designed to help create structured laboratory reports. AI can also help extract relevant information from scientific publications and even generate comprehensive reports on complex topics.

So how can outputs created with AI still retain originality? This is where the human role becomes essential. AI can be a powerful assistant, but the final product should always reflect the creator’s own thinking and analysis. The author should use AI-generated material critically, verify its accuracy, and adapt it to match their own perspective.

Where, then, should we draw the line between one’s own work and that produced with AI (or based on external information), and does such a line even exist? This is a crucial question without a simple answer. Generally speaking, AI should be used as a tool to support – not replace – human work. Transparency about the use of AI is important, and university and journal guidelines should be followed. Ultimately, the value of academic work lies in human insight, critical thinking, and the ability to create new knowledge. AI can assist in this process, but it cannot replace human intellect and creativity.

Case Study: Media Production at CERN – In Search of Building Numbers

Every year I visit CERN to document and produce various types of media content, always trying to find an angle that makes the whole story both understandable and engaging. This time, my attention was drawn to something that remains a small mystery even for many visitors: CERN’s building numbers and their apparent lack of logic. I decided to use this as a starting point and, at the same time, test how artificial intelligence could assist in ideation, scripting, and filming.

How I Used Artificial Intelligence

I used several AI applications – Gemini, Copilot and ChatGPT – to generate ideas and sketch out the overall structure. I read through the suggestions, evaluated them critically, and steered the story in a direction that felt right for me. After several iterations, I ended up with a series that tours CERN from a visitor’s perspective: what buildings a typical visitor (or someone arriving to work at CERN) encounters, and what stories are connected to them.

From Buildings to Stories

Building 33 naturally became the starting point: it essentially serves as a base for visitors and CERN staff alike – often the first stop upon arrival at CERN.

From there, it made sense to move on to the Main Building (500), whose role as the heart of the CERN community is unquestionable.

CERN’s outreach activities now take place largely in spaces open to the public. Hence, the Globe (Building 80) and the newly opened Science Gateway (Buildings 81–87) are included – venues where school visits and the general public most often encounter CERN.

In terms of functionality and the human side of everyday work, I wanted to highlight Building 40. Its spacious atrium, bright corridors and central café create an inviting atmosphere for meetings and encounters. Closely connected to this complex are Buildings 38, 39 and 41 – the hostel buildings that provide accommodation for researchers and guests on campus. Building 42, completed in 2011 next to Building 40, brought administration physically closer to research and researchers.

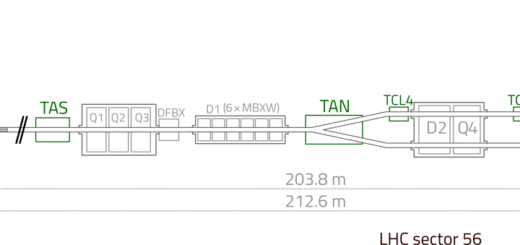

To provide a historical perspective, I turned to the East Hall (Building 157). It is a large industrial space that has undergone extensive renovations – including asbestos removal and insulation upgrades – and houses several experiments and testing environments (for example, CLOUD as well as irradiation and testing facilities) that utilise proton beams.

I also wanted to stop by the ISOLDE area (Building 179 and its surroundings). ISOLDE is one of CERN’s longest-running experiments, with a long and layered history. A unique feature is its location on the border between Switzerland and France – the national border literally runs through the building, meaning that while working at ISOLDE one might “cross” between countries several times a day.

To conclude, I looked towards the future: the HL-LHC upgrade (High Luminosity LHC) and the planned FCC (Future Circular Collider) raise an amusing yet practical question – how will buildings be numbered in the future, and what kind of logic would make sense? Finally, I returned to Building 33 to “close the circle” and tie the themes of the series together.

What AI Could – and Could Not – Do

In this project, AI served primarily as an idea generator. It threw out alternatives and suggestions, from which I picked the most interesting ones. I also used it for targeted searches across the web and CERN’s own materials to verify facts.

At the same time, the project reminded me that AI does not automatically reduce the workload. I repeatedly had to verify claims – sometimes multiple times – and search for background documents or other supporting evidence. This added considerable time to the scripting process and made the overall workflow surprisingly labour-intensive.

Another practical challenge was related to narration. The AI-generated script did not always sound natural when spoken aloud, and I found it difficult to memorise or interpret text that I hadn’t written myself from the beginning. I partly solved this by positioning the script close to the camera during filming and using voice-over narration: I simply read the text from paper on location and replaced my “reading session” in the final video with additional footage (so-called B-roll). It worked, but required its own share of extra effort.

AI also often lacks geographical understanding. In a few cases, I noticed that the suggested locations or views of buildings were simply wrong – not because the model was “stupid”, but because its training data did not include precise location information, leading it to fill the gaps with imagination.

Lessons and Recommendations for Future Productions

- Keep control in your own hands. AI is a good servant but a poor master.

- Provide your own texts and define the task clearly. The more precise the question and the stricter the constraints, the fewer “hallucinations”.

- Fact-checking is a mandatory step. Especially in contexts involving technical details, every claim should be verified from a reliable source.

- Write your narrations yourself in the end. Even if AI helps with structure, the final rhythm and voice should remain yours.

- Allow time. Working with AI does not always speed things up – accuracy and creativity both take time.

Final Words

Overall, the experience was interesting and educational. AI provided ideas and helped outline the structure, but it cannot be relied upon for everything – especially when the goal is a fact-based, visually coherent media series. Next time, I plan to develop ideas further on my own and use AI for specific, well-defined questions. That’s how it works best: as a supportive tool that sharpens the work without taking control.

Join the Discussion: Your Experience of AI in Academia

AI is here to stay as part of academic life, and its potential is vast. We would now like to hear about your experiences and views on the topic.

- How have you or your team used AI applications?

- Where do you think AI could be used in teaching or research?

- What benefits or challenges have you encountered when using AI?

- How has AI affected your studies or research work?

- Do you have ideas on how the use of AI in universities should be guided or regulated?

Share your experiences and ideas in the comments below – or write your own blog post here: present your perspective, even a critical one.

Juha Aaltonen

Helsinki Institute of Physics

The case study part was created with the help of AI (ChatGPT, o3) by providing it with a voice recording transcribed into text, using the following prompt:

“Here is my stream-of-consciousness recording converted to text. It is a draft for a blog post titled ‘Experiences of Using Artificial Intelligence at the Helsinki Institute of Physics – Media Production’. Could you review it, correct the Finnish grammar, and make it a coherent blog post while keeping my content and narrative thread?”

The resulting text was then revised once more for clarity and flow.

This blog post contains AI generated images.