Should we use generative AI in scientific research?

Over the last few years, generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become mainstream, with the public release of ChatGPT in 2022 launching us into an AI boom. Such large language model based AI chatbots are evermore present in our daily lives, and come with the promise of being the next big societal shakeup. Despite the interesting possibilities that generative AI offers, there are still many concerns that need to be addressed before we can fully embrace this new tool in scientific research.

The negative environmental impacts of generative AI are becoming more apparent, with growing concerns related to the energy consumption, water consumption, the need for rare materials, and the electrical waste associated with the data centres needed to train and run generative AI, as recently discussed by the UN Environment Programme. With the ongoing climate crisis, these environmental concerns are hard to ignore.

Another issue relates to the content used to train generative AI models. These models are generally trained on content scraped en masse from the internet, regardless of the copyright status of the sources. This is leading to questions about originality and ownership. Is using copyrighted material to train AI simply plagiarism, or is it no different than artists taking inspiration from each other? While this is an ongoing debate that lawmakers are still struggling with, creative artists and authors are vocally opposed to their work being used to train AI models. As generative AI models produce more and more content, the internet is now being flooded with so-called AI slop – low quality, mass produced content of little value – which in turn is being scraped and used to train the next generation of AI models. Eventually, AI models will run out of original content to be fed, resulting in a diminishing return on investment.

Worries of an AI bubble are become more pronounced, with leading experts now warning this bubble could burst soon. Indeed, many companies are currently heavily investing in AI models and associated data centres, even though returns are diminishing. A recent study conducted at MIT found that 95% of companies’ AI pilots fail, while another study found that the use of AI chatbots like ChatGPT only increased employee productivity by 3%, even in workplaces with substantial investments and early AI adoption. Perhaps the hype around AI is outpacing reality. As costs of training and maintaining these generative AI models and AI chatbots are increasing but returns are stagnating, there is the concern that these costs will eventually shift to everyday users of these products, at a time when people are become increasingly reliant on AI.

The increased reliance on generative AI can also help fuel misinformation, as AI chatbots have a known hallucination problem – they can embed plausible-sounding but completely inaccurate statements within their answers, while confidently assuring that all the information is correct. This means that any text produced by generative AI needs to be thoroughly fact checked. Generative AI can also misrepresent sources, or directly invent plausible-sounding but non-existent citations. This lack of accuracy can be especially problematic if generative AI is used to help write scientific papers, which should be a reliable source of information.

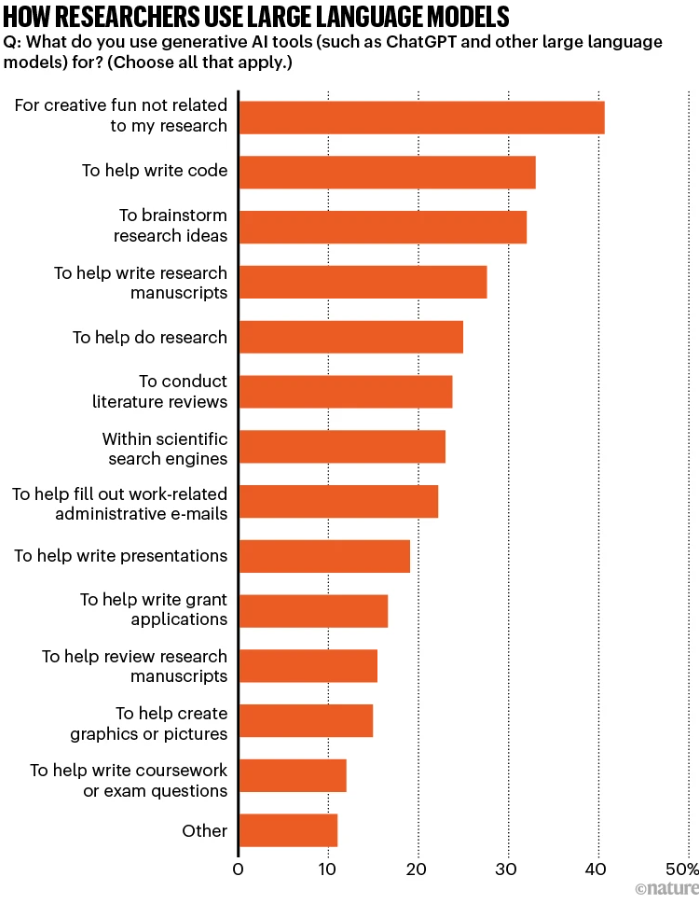

A survey by Nature on the use of generative AI in research showed that over 25% of respondents use generative AI to help write research manuscripts. While some studies show that generative AI tools such as ChatGPT can enhance academic writing, a recent study showed that generative AI reliance can be detrimental to cognitive abilities. As Hannu Toivonen, Professor of computer science at the University of Helsinki, states in the recent blog post Roadmap to the unknown – five recommendations for the use of AI at universities: “If using GPS for navigation causes changes in the brain and impairs its ability to process spatial information, how does outsourcing thinking to language models affect the brain’s ability to think?”.

Another part of scientific research that is seeing increasing use of generative AI is peer review, despite the European Commission’s Living Guidelines on the responsible use of generative AI in researchadvising against this. A recent AI conference is under scrutiny after 21% of the manuscript reviews were found to be generated by AI. Meanwhile, a Nature survey showed that the majority of people do not agree with using AI to generate a complete peer review report; however, 57% felt it was acceptable to use AI to assist with the peer review process.

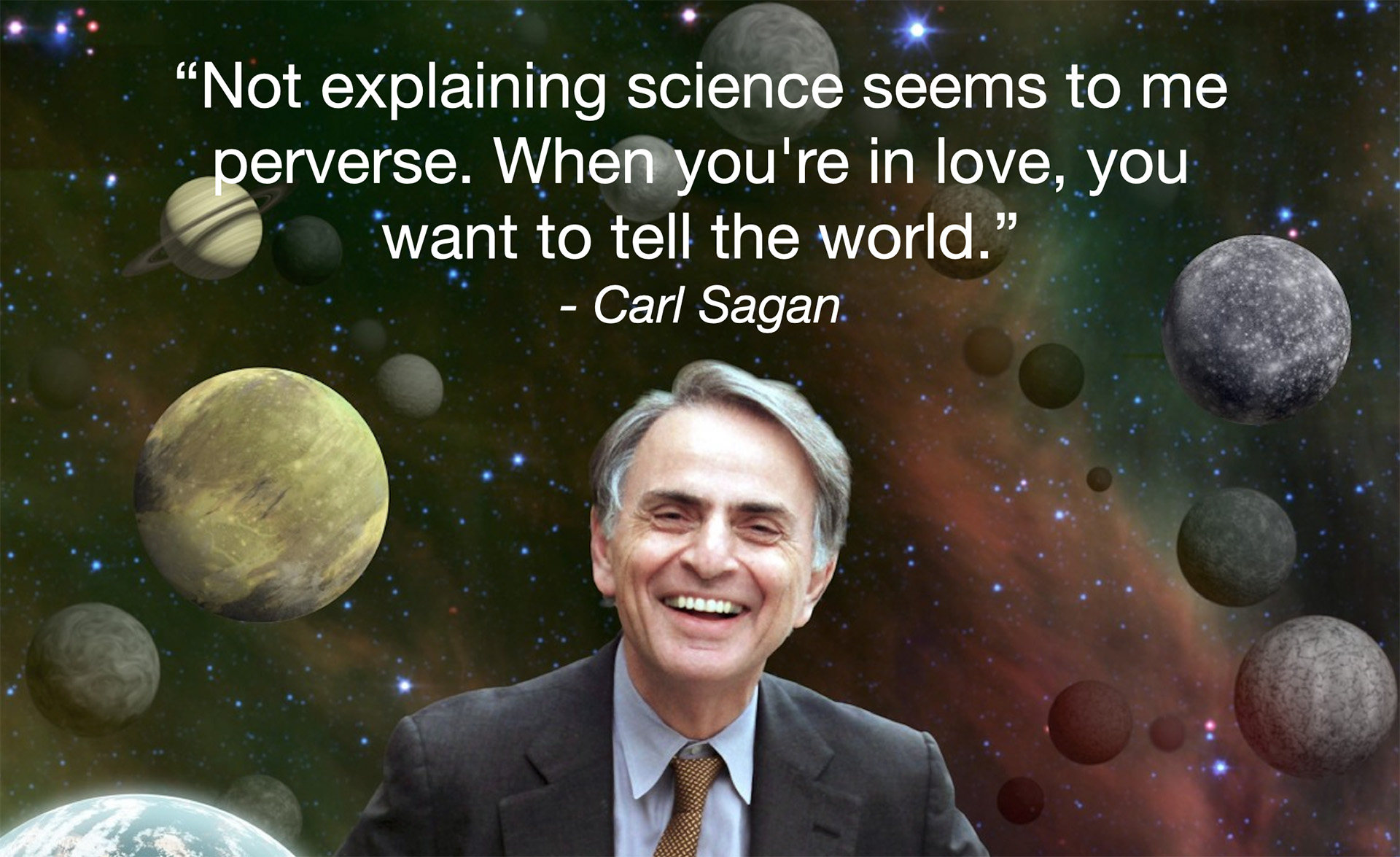

With generative AI being used more in every step of the scientific writing process, we have to wonder if we are now heading to a state where scientists use generative AI to write (or co-write) their manuscripts, these are reviewed by AI, and then other scientists use AI to summarise these papers in a literature review. Once the human element has been removed from this process, what are we left with? While science deals with objective facts and observations, the way we communicate these will always be a subjective process. Which results to highlight, how to present them, and importantly, how to make people interested in the results is an exercise in human creativity. Carl Sagan inspired many scientists with his words “we are all stardust”, and those words came from a place of passion. If we remove the human element, we remove the passion that lies at the heart of scientific research.

For better or worse, generative AI is dramatically impacting society, as highlighted by the “Time Magazine’s” choice to award their “Person of the Year” prize to the architects of AI. As scientists, we have to adapt to the changing times, but we also have an obligation to ask ourselves how much of the scientific process can and should be outsourced to machines. Are we sacrificing scientific integrity by using generative AI? Do the benefits of generative AI outweigh the negatives? What is the price we are willing to pay for convenience? These are questions scientists will have to grapple with in this evolving landscape. Currently AI is like a shiny new hammer and everything looks like a nail, but perhaps some caution is needed before we start swinging this new hammer around.

Deanna C. Hooper

University Researcher, Helsinki Institute of Physics, University of Helsinki